The internet? Friend or foe? Now I need not limit myself to boring friends and family with my year-end letters. I can now bore complete strangers. And why settle for posting only one year-end letter when it’s almost as easy to post two, three, five, or even twenty-five? This month I’m planning on posting one letter a day until Christmas. This is the first year-end letter I wrote after my first summer as a forest firefighter in 1987.

December 1987

Dear Friends and Family,

I’m going to risk the wrath of my friends by sending out one of those dreadful Christmas letters everyone hates, but I feel I must do so because my writing habits have become so lax that many of you seem to think I’m still lost in the Congo. I’m alive and well in Washington D.C. enjoying modest success in my cartooning and writing career. Much as I hate to admit it, some of my work is now even readily available to the public in The Globe and The National Examiner, supermarket tabloids that will tell you how to lose weight while being abducted by aliens who are Jackie O clones.

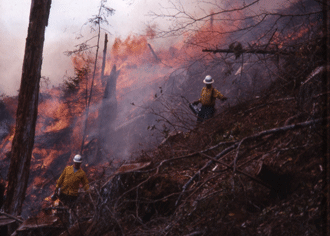

I took a break from cartooning during the summer to live in Oregon with Susan, the friend I hitchhiked with through Africa. I worked for the Forest Service as a firefighter. On a typical day, I’d be starting controlled fires, going through dense underbrush and up a 60-degree slope holding a drip torch, a lit two-gallon can of gasoline, sort of a large Molotov cocktail. My boss would often pat me on the shoulder and say, “Don’t worry, this is a perfectly safe job.” I don’t think Mom would have thought so, especially if she’d seen us breaking for a talk and dripping fire on our boots while ignoring the fire sounding like a locomotive behind us. It’d be a beautiful sight, though, with orange flames contrasting sharply with a deep blue sky and fire devils– tornado-like whirlwinds of embers and debris–billowing 25 to 50 feet in the air. The closest we came to having someone go up in flames was when the pants of a woman caught on fire. She dropped her hose shrieking, “I’m on fire!! I’d better smother it!!!” Instead of dousing her pants with her hose, she rubbed them in the dirt, an action we learned in fire school from the 1940s movie Fighting Fires With Dirt.

Some fires are more unglamorous than others. One of Oregon’s first big ones of the season was in July in Umpqua National forest. My 20-person crew settled on the bus and began calculating how much we might make on this fire: “Let’s see, if we get time-and-a-half for overtime, time-and-three-quarters for hazard-duty pay, a 25% differential for night duty, we’re on the clock for 18 hours today, and my Saturday was my Monday … or was it Tuesday? …”

Eventually, people started swapping “war stories: “ … She was a macho-female who built fire lines better than anybody. She was hit in the back by a rolling rock and later that day complained of severe back pains. They medi-vaced her out of camp to a hospital. A couple of hours later she gave birth to a baby.” “… A helicopter with twenty bladder bags [rubber backpacks that hold seven gallons of water] got caught in a fire devil, and dropped its load on a Volkswagen bug squashing it as flat as a hubcap.” “… She was wearing nylon underwear and it fused to her body when she was blinded by a flying ember, fell and grabbed a burning tree…” “… Someone yelled ‘ROCK!’ I heard a loud crack, and my partner’s hard-hat was still in the air, but he was down at the bottom of the hill. It took 20 of us over 10 hours to get him out …”

When we arrived it was raining and we were sent out with another crew to dig fire line. After digging line for 15 minutes I asked, “Where exactly is the fire?” Somebody else said, “That’s a good question!” We were engulfed in smoke and heavy fog and could see no more than five feet in any direction. One squad boss pointed east, another pointed west. Standard Fire-fighting Order Number 2 is: “Know where your fire is at all times.” We stopped digging and started walking down the hill to look for the fire. How could something as big as an 11,000-acre fire be so hard to spot? We walked downhill for 30 minutes before it was determined that there wasn’t any point in having 40 of us lost–better to only lose one or two. Two brave souls set off, leaving the rest of us shivering in the rain for an hour and a half. This was not the sort of war story I was hoping to come back with. “… And then there was the time I caught pneumonia…”

The scouts returned triumphantly announcing they’d found fire. They’d flagged the entire route. There wasn’t any way to miss it, they said. Two hours later, after cutting through brush as thick as any in Africa’s jungles, it became obvious that we had somehow missed it. We turned to our guide and asked, “Where the hell are we?” He confessed that he didn’t have the slightest idea. He’d lost the map sometime back.

Finally, we found a few flames. Thank God. If you’re not actually on the fire line you don’t get hazard duty pay. Plus, we were freezing. All 40 of us huddled around something the size of a campfire and we started throwing twigs on it. Only after we’d regained the feeling in our hands did we douse the flames.

Something in the diet was disagreeing with me, so I kept having to, as they say in the Forest Service, “go search for Smokey the Bear.” I was in the middle of my business when a snag, a dead tree, fell near me. The cannon-like clap startled me and I fell back into a batch of poison oak. “What a way to go,” I thought.

While we dug line our guide was trying to find a way out. We had about two hours until sunset, at least a three-hour hike uphill, and no headlamps. Helicopters buzzed overhead trying to find alternate routes but, in the end, could offer no other assistance than the advice that we get out of there. We did, slipping and sliding since the rains had turned the ground into slick mud. We arrived back in camp around midnight, downed steaks, went to sleep for a couple of hours, and started all over again in the morning.

Happy holidays. Hope all is well with you and yours,

T-

Cheap Fire Cartoons for use in textbooks, presentations, ads, etc.

Buy Holiday Cartoon 1629

Get it Printed on Stuff from CafePress