World War 1 started 100 years ago this month.

Central coastal Oregon, a continent and ocean away from the fighting, had soldiers camped there. They were logging Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), the lightest, strongest wood for its weight and was used to make airplane frames. It only grows along a four-mile (1.2-km) fog-shrouded band on the coast from northern California to Alaska. Before the war spruce was viewed as good for nothing but making fish boxes.

The early war years were also years of labor activism and radicalism in the West. The Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) represented the “homeless, womanless, voteless migratory workers in the West,” including loggers.

The first loggers in Oregon were from New England and the Midwest. They brought with them knowledge of bull teams, caulk boots, and cuss words. The equipment they had, though, was designed for eastern trees that were puny in comparison to the northwest giants. One tool they created was a springboard. To fell a tree two men stood several feet in the air on boards just a few inches wide. They had to get above the pitch-filled, wide trunk base of a tree. Using axes they made an undercut on the side they wanted the tree to fall, each man swinging alternately in perfect harmony. Then they would move around to the backside and start cutting with saws liberally doused with oil to keep them from binding in the pitch. When just a few inches were left, the tree would topple. No faller worth his salt couldn’t drop a huge tree on a dime on the head of a crooked timekeeper.

The logs were then bucked and taken to a skid road where they were hooked to an oxen or horse team called “hay-burners.” Skid roads were constructed of poles laid crosswise like the ties in railroad tracks. A greenhorn greased the poles, walking between the oxen and the logs, daubing the poles with whatever kind of oil was available: crude, porcupine, or whale. On steeper slopes, the teams were forced to gallop to keep from being run over by the logs. Some would be caught and the camp cook would quickly butcher them.

The logs were skidded to landings and loaded on railroad cars. Villages sometimes grew up about the lower end of skid roads. Sensitive folks didn’t inhabit them because of the noise, dirt, and profanity thought necessary to motivate the oxen teams. The term skid row is a corruption of skid road.

Most loggers were drifters who worked from dawn to dusk for about a dollar a day. Turnover in some camps was 600 percent a year. There were an infinite number of reasons people gave for leaving: weather too hot, weather too cold, lumber too heavy, pay too light, grub too greasy, coffee too weak, too many Swedes, too many Finns, too many of the boss’s relatives in the crew, too far from Portland, too close to Portland, timekeeper crooked, and flat beer in the local tavern.

The bunkhouses, crowded with twenty to forty men, were dark and smelled of drying wool clothing, wood burning, sweat, kerosene, well-used spittoons, and whiskey on the breath.

License Environment Cartoon 6278

Get it printed on stuff from Cafepress

Loggers were a superstitious lot. At an operation near Gardiner that had three fatalities, someone claimed he had seen an eagle fly overhead before each accident. Thereafter, whenever an eagle flew over, the crew quit work for the day.

License Horoscope Cartoon 3704

Get it printed on stuff from Cafepress

It was said that a logger’s life expectancy was no more than seven years. One estimate is that one logger died every other day between 1870 and 1910.

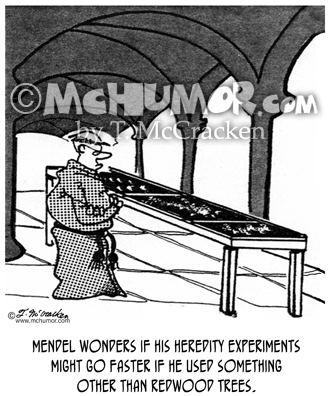

License Forestry Cartoon 1818

Get it printed on stuff from Cafepress

During World War I railroad tracks were laid along the coast to transport logs. The line was completed on November 8, 1918, three days before the end of the war. One million board feet of spruce had been bucked into logs, but not one was shipped on the line.

Cheap Union Cartoons for books, websites, presentations, etc.